Now, don’t get me wrong (continuing from my entry two posts ago); it’s not that I’m complaining about “having to” sew for a living–I’m attempting to publicly reason through what made me rush home from linguistics class to sew without a break back in college, and what it is that changed so that now there’s a temptation to take a break from taking a different kind of a break before getting back to work.

And don’t say “being 23,” because it’s that kind of attitude that puts bags under your eyes at midnight on your 29th birthday and makes you old when you’re old.

This woman is 70. To all those people who have ever said to me–or to anyone, for that matter–“Well, you’re not 20 anymore, what do you expect?” (though my first-person encounter with that sort of rubbish was at age 27, so what do YOU expect?), take a good long look at the above photo and then an even longer look at the following photo response:

I know a self-described “corporate whore” who does awesome art–my house is about 80-90% decorated with his stuff–who described the divide in college when all his artist friends started art-related careers, while he picked a money-related career. Now he does more art than any of them do.

That’s the danger of successfully turning a hobby into a job. It doesn’t take long before the thing you love becomes the thing you have to do.

Robert A. Johnson, in his book She describes the journey to maturity as starting out in childhood with unconscious perfection, shifting in adulthood to conscious imperfection. The final stage is conscious perfection, combining the best of both. I like to apply this model to pretty much anything that comes in 3 and happens across a timeline, and I posit that the hobby-to-job transformation exemplifies it.

To go off for a moment on a related tangent, I have met a lot of people who want to sew. When I was rolling in writing circles and telling everyone about how I was going to be a writer (which I still will . . . ), I met a lot of people who wanted to write. Get people talking enough, and you’ll hear about how people want to paint, but . . . who want to _____, but . . .

The thing is, if you want to write, you write. If you want to sew, you sew. If you want to paint, you paint. If you want to learn guitar, you play a guitar. Actually, what all these people want is not to sew, but to want to want to sew; to want to want to write, to want to want to paint.

There’s nothing wrong with this; nobody can do everything they want to want to do. Nobody has enough energy to actually want to do all of these things, and they wouldn’t be any good at any of them if they didn’t set aside the want-to-wants. (Though that previous statement does not apply to you if you only have want-to-wants; in that case, pick one and want it.)

I want to want to play the piano; I’ve wanted to want to play the piano for over two decades–I even went so far as to take a year of classes and to buy a nice keyboard and a lot of music books. I practiced periodically, but I never wanted to–I only wanted to want to, so now the closest I’ll come to playing a piano is hanging one’s guts on my wall and strumming them amusically.

I want to want to learn gymnastics. I want to want to be a martial arts master. I want to want to be a dead shot with some kind of projectile. I want to want to have an impeccably trained dog. I want to want to be able to sing. I want to want to keep a beat on a drum (I’ve heard it said that there are two kinds of people in the world–drummers and people who want to be drummers). I want to want to build elaborate furniture. I want to want to understand electricity and wiring. I want to want to be a chemist. I want to want to want to be able to hold a spider without going into convulsions.

So know that what I’m saying here is not a value judgment. It says nothing against you that you’d rather buy your clothes in a store than make them yourself. It says nothing against you that you don’t want to churn your own butter. It says nothing against you that you get your oil changed at a shop–or, if you do change your own oil, that you didn’t build your own car from scratch.

Back to sewing. First you want to want to sew. You admire fashions; you admire other people who sew; you buy fabric but don’t do anything with it; you talk about what you could do with it, what you will do with it; you think about buying a sewing machine, but you use the excuse that you don’t know what kind is best or they’re too expensive; you maybe even have a sewing machine, but you don’t know how to use it, and you don’t get around to learning. You think about at least sewing your own buttons back on your shirts when they fall off in the wash, but it just seems like so much work and hassle, and it’s easier to hire someone to do it. You roll around outside the edge of sewing, but you never cross the border.

When you really want to, you start figuring out a sewing machine, you start playing with patterns. Make a pillowcase. Pajama pants. Repair a tear that’s on a seam. Discover how easy it is to add darts to certain cuts of shirt and jacket, and go nuts. Everything’s exciting–OMG, I can cut out a pattern on the bias and it makes it drape completely different!

To take it from dabbling, wanting to dabble, or vague slightly dabbling to actually sewing even part time, you have to change your mind. There is a lot of tedium in sewing, and one of the big points I’ve heard people bring up against themselves personally being able to sew is that they don’t have the patience. You don’t sew because you have patience; you have patience because you sew.

I was a kid who grew up spending a lot of time sitting still, entertaining myself quietly, reading, drawing. I have an unusually high tolerance for sticking with a project for an extended period. But making a half dozen skirts all with 6 panels and 18 godets (triangles) sewn in between the panels in sets of three, could make the aspergheriest bean counter balk.

You try the trick where you see how many you can do in an hour, then try to break that record. You try counting down: there are 108 triangles. Yeesh. Okay, no, there are 18 in this skirt. Let’s start there. So you plow away at these triangles for a really, really, really long time, then stop to count how many are left. 14. Seriously? But I’ve been working on this forever. So you work on it for even looonger this time. Stop and count them: 9 left.

And you’ve just spent probably a quarter of your sewing time counting and recounting triangles instead of finishing a freaking skirt. Not to mention dwelling on the fact that you’re sewing triangles and getting quickly sicker and sicker of it.

What has to happen between counting triangles and wondering why you ever wanted to sew instead of just wanting to want to is a cognitive shift. There are any number of Zen anecdotes about the rice-preparing monks reaching enlightenment before the meditating monks; there’s something about repetition to enjoy (there’s even a Hot Chip song about it) but you have to change the way your brain works to make this possible. Since we can’t get into our own personal bios or locate the dos prompt, the most reliable way to do this is by doing it.

http://youtu.be/1mdgLn5BFRQ

Back to the three-part growth cycle. I suspect that pretty much every job provides the opportunity to get bogged down on level two.

I’ve never sold a house, but if I did sell one, I’d probably be pretty excited. I’d probably be pretty happy with my sales skillz for the next ten houses. A couple decades later, and do you still love your real estate job? Teaching kids all year, getting to know them, and then they move on and you start over, teaching the next round the same stuff. Year after year, same song thirtieth verse, a little bit louder and a little bit worse.

Feeding big cats at a sanctuary–how long until the excitement of feeding this guy wears off and you lose the wish that you could just cuddle him?

It’s easier to force yourself through the second stage for longer when you work for someone; when there’s someone else making you do it. When some of your time clocked in can be spent getting paid to go to the bathroom or playing minesweeper. This is why there are so many genius artists who can’t make a living; when you want to keep your attitude about art at stage 1 but get paid like you’re in stage 2, it’s not going to work.

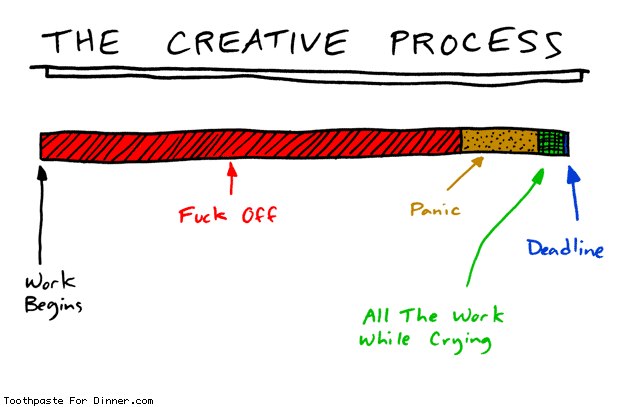

The question is what does it look like to reach level 3? The confusing part is you can’t imitate anyone else who’s found it, because it’s going to be different for you; some people are going to get all the work done during the red part of the above graph, then relax in the yellow. Some people are going to have that same style of action, just without the crying part. So if you’re standing at level 1 and trying to imagine at yourself at level 3 and thinking you know what that looks like, I leave you with this picture to ponder: